Gallego, R., Gonzalez, S. and Maestripieri, L. (Ed.) Social Innovation and Welfare State Retrenchment, Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds, pp. i-xvii.

The book Social Innovation and Welfare State Retrenchment: A Comparative Analysis of Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe and Beyond is now available. The volume gathers case studies from Barcelona, Oslo, Seine-Saint-Denis, Venice, Tokyo, Portsmouth, and Tel Aviv to examine and question the capacity of these social innovation initiatives to address social inequalities—particularly in the field of early childhood education and care (ECEC).

Since the early 2000s, social innovation has gained increasing relevance in political and research debates on the transformation of the welfare state. While most social innovations have been citizen-led, new initiatives have also emerged from institutions. But what are the implications of social innovation for equity and well-being? How does policy learning occur through social innovation across different welfare regimes? How can policy be both responsive to diverse needs and ensure equity and universalization?

Social Innovation and Welfare State Retrenchment explores these questions through the lens of ECEC, an area where the welfare state has failed to achieve universal coverage, where social investment is key to equal opportunity, and where intersectional influences across various dimensions of inequality—such as education and gender—are critical. The book introduces an original research design to study the institutionalization of social innovation in ECEC across different European and non-European contexts, offering evidence on how the interaction between social innovation and public policy deeply affects equity and well-being in advanced capitalist economies.

Access to ECEC services currently varies across the globe: while some countries have nearly universal coverage, others are still struggling to reach optimal enrollment levels. Many governments have made the universalization of ECEC a political priority, and the European Union is currently considering introducing a target of 50% participation in early education for children under three by 2050. However, how to achieve a meaningful level of ECEC use remains an open question—especially considering the wide range of preferences and needs among families.

One potential solution to improve policies is to consider alternative services promoted by citizens, aimed at addressing needs unmet by either the market or the state. In this sense, social innovation can inspire policy innovation and foster a diversification of services for children under three, better suited to the increasingly differentiated needs of families. In some cases, this diversification responds to specific family preferences and needs, recognizing that a one-size-fits-all, school-type approach may not be adequate. In other cases, it is the result of civil society efforts in the face of public inaction to expand coverage.

As a result of the combined expansion of public ECEC policies and diversification through grassroots initiatives, ECEC services now encompass a wide variety of programs: full-time and part-time nurseries, family centers, parenting groups, childminders, and parenting support programs—ranging from school-type educational services to home-based care (with significant internal variation). This diversification, not always delivered by the public sector, reflects the need to offer high-quality, accessible ECEC adapted to all children and families regardless of their background or circumstances.

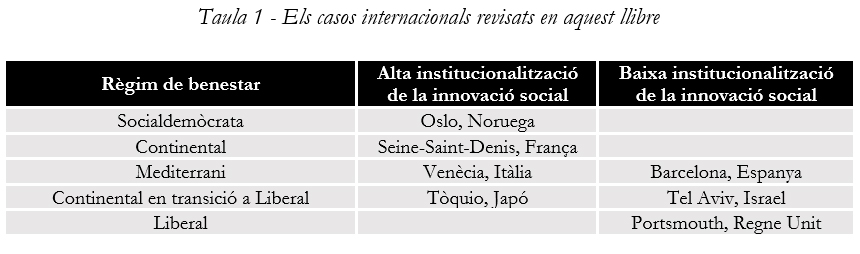

The cases featured in the book differ not only in terms of their welfare regime but also provide the most effective research design to study the institutionalization of social innovation (see Table 1), i.e., the extent to which citizen-led initiatives have been integrated into the public provision of ECEC. In four of the cases (Oslo, Seine-Saint-Denis, Venice, and Tokyo), the authors’ analysis shows how institutionalizing social innovation can foster more integrated public services that respond to the diversity of family needs. In the other three cases (Portsmouth, Barcelona, and Tel Aviv), the focus is on how social innovation fills a gap left by the market and the state, demonstrating its capacity to meet family needs in contexts of limited public provision. These latter cases show the strong analytical potential of studying institutionalization processes while they are still unfolding.

The book examines differences in ECEC provision approaches and emphasizes the importance of context-specific strategies to achieve optimal outcomes for young children and their families. It also addresses how and to what extent public authorities develop innovative ECEC policies by learning from diverse social innovation experiences to better respond to childcare needs. Finally, the book reviews the risks associated with social innovation, as well as the challenges for ECEC policies and institutionalization dynamics in a context of welfare state retrenchment, discussing the implications of the ability of social initiatives to address social inequalities.

The fragmentation of ECEC systems and the lack of universal coverage create significant access inequalities in most of the observed cases. In a context of increasing social complexity, universalizing ECEC will likely require a diversification of service provision to meet different needs and demands. The book’s analysis shows that the impact of different social innovation institutionalization strategies in ECEC tends to depend on the type of welfare regime they are embedded in. Public regulation and funding are necessary tools to ensure equal access and high quality across this diversity.

Social innovation has helped expand limited coverage and brought many benefits, addressing a wide range of challenges. However, it can also carry inherent risks and challenges depending on how it is regulated. If social innovation schemes fail to ensure equitable access to services, those risks may manifest as exclusion of certain groups, leading to social polarization, fragmentation, or even a drop in service quality—thereby increasing socio-educational inequalities.